Some of my favorite country songs.

Deana Carter, "Strawberry Wine"

Don Williams, "Good Ole Boys Like Me" (the song my mom & I danced to at Leigh and my wedding)

Alan Jackson, "Here In the Real World"

Waylon Jennings, "Are You Sure Hank Did It This Way"

The Judds, "Grandpa (Tell Me About the Good Old Days)"

George Jones, "Who's Gonna Fill Their Shoes?"

Toby Keith, "Little Too Late" (my favorite single from 2006, btw)

Dixie Chicks, "Cowboy Take Me Away"

Glen Campbell, "Wichita Lineman"

Garth Brooks, "The Dance" (my Dad would let me spend hours in the elementary school gymnasium on the weekends shooting baskets, and I'd bring a small tape player and listen to Garth Brooks' first album over and over)

Statler Brothers, "Flowers on the Wall" (a hot version)

Roseanne Cash, "Seven Year Ache"

Alison Krauss & Union Station, "Stay"

Iris Dement, "Our Town"

Thursday, January 18, 2007

Saturday, January 13, 2007

The beginnings of a draft for a 'work in progress'-type, fairly casual presentation to my peers in the English department next Friday. I'll put up the whole thing if I think it doesn't blow:

My most general emphasis is 20th century American lit; a little more specifically, innovative or experimental poetry in America, though in my thinking no conception of any sort of innovative tradition of American poetry can make any type of sense without emphasizing the increasingly global aspects of that tradition—it would make little sense, for instance, for me to consider the two (in my view) most interesting American modernist poets (Gertrude Stein & Ezra Pound) without accounting not only for the influence of their respective exiles upon their own work, but also the influence of their self-positioning as 'citizens of the world' upon the very basic notion of what we may mean by “American poetry.”

With this in mind, my notion of innovative American poetry includes figures such as the Negritude poet Aime Cesaire & the Peruvian poet Cesar Vallejo (as well as their American translator, Clayton Eshleman, in my view one of the most fascinating contemporary poetic figures), the tri-lingual American born poet Eugene Jolas, who lived in France for his adult life & founded transition magazine, which ran Finnegans Wake in serial form under the title “Work in Progress” & was among the early supporters/defenders of Gertrude Stein & Laura Riding Jackson, & global collective movements such as concrete & sound poetry, Fluxus, OuLiPo, and so forth, all of which have not only included American born poets but which have also significantly altered what is meant by American poetry, or at least modeled and sanctified potential structures for various experimental movements.

So within this conception of American poetry, what I’m most interested in are theories and applications of immediacy (& therefore, mediation)—the influence of new technologies and media on these notions, the ways in which immediacy has been claimed for collective and political use (Surrealists, Cesaire, the Beats, etc) (especially as centered around the connections posited between oralities/immediacies/divinities), and the degree to which the innovations in 20th century poetry seem to be connected to a reclamation of bodily immediacies, whether it be the motor automatism of Stein or the emphasis upon breath as the measure of the poetic line in Charles Olson.

The paper I’m working on falls within this topic as it is the beginnings of my testing out of several intuitions—in her book The Dance of the Intellect: Studies in the Poetry of the Pound Tradition, Marjorie Perloff asks “Pound or Stevens: Whose Era?” Clearly, for a critical tradition that includes Harold Bloom, Helen Vendler, and others, the answer is “Wallace Stevens.” For Perloff herself, Hugh Kenner, Guy Davenport and others, the answer is “Ezra Pound.” Increasingly, it is my hunch that the more we expand the term “era” towards the present moment, the more likely it is that the answer which opens up the most interesting questions will be “Gertrude Stein.”

In his recent utopias book, Archeologies of the Future, Jameson makes a distinction I’ve found really useful—utilizing the well-known Coleridgean difference between the major faculty of Imagination and the more minor faculty of Fancy, Jameson writes of a “structural shift” where what was formerly a utopian Imaginative task, creating an alternative social and economic structure, has been altered by “the emergence of industrial capitalism itself, which effaces beyond any recall but the nostalgic kind that simpler pastoral or village existence”—now, “since a single system or mode of production” has “supplanted all the others,” such complex constructions are more fanciful, while the Utopian Imagination (the major creative faculty) grapples with “the former space of Utopian Fancy, namely in the attempt to imagine a daily life utterly different from this one . . . without alienated labor or the envy and jealously of others and their privileges. It is an attempt which then slips effortlessly into metaphysics, such as the calm of the Heideggerian return to being.”

By adopting this framework, I’m trying to get at late capitalism’s shift in the terms and applications of the resistant/creative Imaginative function (whether strictly Utopian or not), how Ezra Pound’s patterning and overlaying of various economic and historical theories in his poetry could possibly been seen—in spite of all his own poetic innovations and his prescient realizations of the relevance of industrial and artistic innovations for poetry—as still somewhat blind to the realities of his own historical moment and are dependent upon the assumptions of a previous one, especially when contrasted with Stein's theories and practice.

If, as Bob Perelman suggests in The Trouble With Genius, the prototypical Poundian cultural hero “changes society without touching it” via his or her manipulation and mastery of aesthetic forms, then a Deleuzian-Guattarian conception of experience, where “order-word assemblages” and other intermingling bodies do not directly communicate or convey information but rather reify social orders through indirect discourse, will illuminate even as it disrupts the very ground that a Poundian hero assumes. My paper attempts to read Pound’s essay “Machine Art,” written while in exile in Italy in the late 1920s and only fairly recently collected, in conjunction with Deleuze and Guattari’s “November 20, 1923: Postulates of Linguistics” in A Thousand Plateaus. Additionally, a specific episode from Siegfried Kracauer’s The Salaried Masses: Duty and Distraction in Weimar Germany, first published in 1930, will be introduced as a counter-Poundian example of indirect cultural discourse from the same period, where the management and instructors of a secretarial pool are shown to be the actual Poundian heroes able to not only sense but also manipulate the underlying order-words that make up the paideuma of their historical moment.

My most general emphasis is 20th century American lit; a little more specifically, innovative or experimental poetry in America, though in my thinking no conception of any sort of innovative tradition of American poetry can make any type of sense without emphasizing the increasingly global aspects of that tradition—it would make little sense, for instance, for me to consider the two (in my view) most interesting American modernist poets (Gertrude Stein & Ezra Pound) without accounting not only for the influence of their respective exiles upon their own work, but also the influence of their self-positioning as 'citizens of the world' upon the very basic notion of what we may mean by “American poetry.”

With this in mind, my notion of innovative American poetry includes figures such as the Negritude poet Aime Cesaire & the Peruvian poet Cesar Vallejo (as well as their American translator, Clayton Eshleman, in my view one of the most fascinating contemporary poetic figures), the tri-lingual American born poet Eugene Jolas, who lived in France for his adult life & founded transition magazine, which ran Finnegans Wake in serial form under the title “Work in Progress” & was among the early supporters/defenders of Gertrude Stein & Laura Riding Jackson, & global collective movements such as concrete & sound poetry, Fluxus, OuLiPo, and so forth, all of which have not only included American born poets but which have also significantly altered what is meant by American poetry, or at least modeled and sanctified potential structures for various experimental movements.

So within this conception of American poetry, what I’m most interested in are theories and applications of immediacy (& therefore, mediation)—the influence of new technologies and media on these notions, the ways in which immediacy has been claimed for collective and political use (Surrealists, Cesaire, the Beats, etc) (especially as centered around the connections posited between oralities/immediacies/divinities), and the degree to which the innovations in 20th century poetry seem to be connected to a reclamation of bodily immediacies, whether it be the motor automatism of Stein or the emphasis upon breath as the measure of the poetic line in Charles Olson.

The paper I’m working on falls within this topic as it is the beginnings of my testing out of several intuitions—in her book The Dance of the Intellect: Studies in the Poetry of the Pound Tradition, Marjorie Perloff asks “Pound or Stevens: Whose Era?” Clearly, for a critical tradition that includes Harold Bloom, Helen Vendler, and others, the answer is “Wallace Stevens.” For Perloff herself, Hugh Kenner, Guy Davenport and others, the answer is “Ezra Pound.” Increasingly, it is my hunch that the more we expand the term “era” towards the present moment, the more likely it is that the answer which opens up the most interesting questions will be “Gertrude Stein.”

In his recent utopias book, Archeologies of the Future, Jameson makes a distinction I’ve found really useful—utilizing the well-known Coleridgean difference between the major faculty of Imagination and the more minor faculty of Fancy, Jameson writes of a “structural shift” where what was formerly a utopian Imaginative task, creating an alternative social and economic structure, has been altered by “the emergence of industrial capitalism itself, which effaces beyond any recall but the nostalgic kind that simpler pastoral or village existence”—now, “since a single system or mode of production” has “supplanted all the others,” such complex constructions are more fanciful, while the Utopian Imagination (the major creative faculty) grapples with “the former space of Utopian Fancy, namely in the attempt to imagine a daily life utterly different from this one . . . without alienated labor or the envy and jealously of others and their privileges. It is an attempt which then slips effortlessly into metaphysics, such as the calm of the Heideggerian return to being.”

By adopting this framework, I’m trying to get at late capitalism’s shift in the terms and applications of the resistant/creative Imaginative function (whether strictly Utopian or not), how Ezra Pound’s patterning and overlaying of various economic and historical theories in his poetry could possibly been seen—in spite of all his own poetic innovations and his prescient realizations of the relevance of industrial and artistic innovations for poetry—as still somewhat blind to the realities of his own historical moment and are dependent upon the assumptions of a previous one, especially when contrasted with Stein's theories and practice.

If, as Bob Perelman suggests in The Trouble With Genius, the prototypical Poundian cultural hero “changes society without touching it” via his or her manipulation and mastery of aesthetic forms, then a Deleuzian-Guattarian conception of experience, where “order-word assemblages” and other intermingling bodies do not directly communicate or convey information but rather reify social orders through indirect discourse, will illuminate even as it disrupts the very ground that a Poundian hero assumes. My paper attempts to read Pound’s essay “Machine Art,” written while in exile in Italy in the late 1920s and only fairly recently collected, in conjunction with Deleuze and Guattari’s “November 20, 1923: Postulates of Linguistics” in A Thousand Plateaus. Additionally, a specific episode from Siegfried Kracauer’s The Salaried Masses: Duty and Distraction in Weimar Germany, first published in 1930, will be introduced as a counter-Poundian example of indirect cultural discourse from the same period, where the management and instructors of a secretarial pool are shown to be the actual Poundian heroes able to not only sense but also manipulate the underlying order-words that make up the paideuma of their historical moment.

Tuesday, January 09, 2007

Since Tim tagged me, I will now be that last contemporary American poet to fill out that one meme.

Five little known Tostian tidbits:

1) While living in Fayetteville, I once sold my car to a friend for a dollar at a party. Then a bunch of us flipped the car over, for fun.

2) At me & Leigh's wedding reception, about thirty or so of our friends decided to get naked in the tiny swimming pool on the grounds of the bed & breakfast we were at; Leigh, her parents & I passed around the champagne bottle as our friends (from Arkansas, North Carolina, and one brave soul from Harvard) had chicken fights, tried to avoid the broken glass, and occasionally ran out of the pool to hug one of us for the best. wedding. ever.

3) I will engage in karaoke any time, any place. My favorite songs: Greatest Love of All, To All the Girls I've Loved Before, Wichita Lineman, Desperado. Michael Heffernan and I did a splendid version, I think, of "My Way" at our friends' Mark & Emoke's wedding.

4) The director of the Arkansas MFA program, and his wife (an elementary school teacher), both in their early to mid sixties, did keg stands at said wedding. As did I. As did the groom. As did (I think, but am not totally certain) the bride.

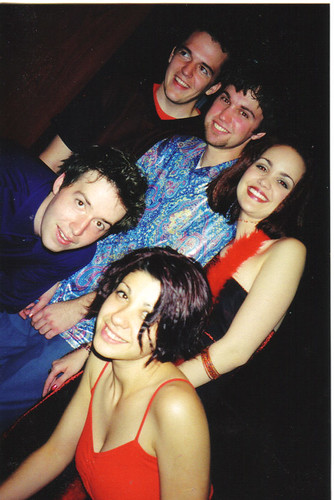

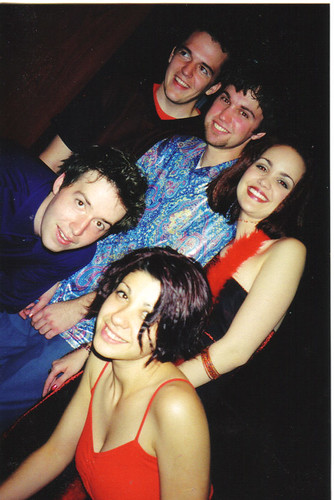

5) In the year between undergrad at College of the Ozarks and my MFA at University of Arkansas, my friend Riley and I rented a trailer outside of Branson, often sharing the trailer with a handful of friends at different points, including Riley's girlfriend at the time, April McIntosh. Below is a picture of myself, Riley, our friend Chris, April, and our friend Eda at C of O dance.

Chris and Eda are now married, with child. Riley is now in Minnesota, beginning his fortune in computers. I am, sadly enough, a poetry blogger. April? April is a Deal-or-No Deal girl, and is also now starring as Daisy Duke in the sequel to the Dukes of Hazzard movie.

________

My good friend Micah has the following quote from Barack Obama:

"In the back-and-forth between Clinton and Gingrich, and in the elections of 2000 and 2004, I sometimes felt as if I were watching the psychodrama of the Baby Boom generation - a tale rooted in old grudges and revenge plots hatched on a handful of campuses long ago - played out on the national stage."

School of Quietude and School of the Post-Avant, anyone? Or, to be less Silliman-centric (he's certainly not the only one, just the readiest example), replace Clinton with usual suspect L, & Gingrich with usual suspect P.

________

I've always been a casual subscriber of the oft-noted deep underlying similarities between much country and hip-hop; Ice Cube/Folsom Prison, etc.

As though to seal the deal:

(thanks to L. Amelia Raley for the lead on the above)

Five little known Tostian tidbits:

1) While living in Fayetteville, I once sold my car to a friend for a dollar at a party. Then a bunch of us flipped the car over, for fun.

2) At me & Leigh's wedding reception, about thirty or so of our friends decided to get naked in the tiny swimming pool on the grounds of the bed & breakfast we were at; Leigh, her parents & I passed around the champagne bottle as our friends (from Arkansas, North Carolina, and one brave soul from Harvard) had chicken fights, tried to avoid the broken glass, and occasionally ran out of the pool to hug one of us for the best. wedding. ever.

3) I will engage in karaoke any time, any place. My favorite songs: Greatest Love of All, To All the Girls I've Loved Before, Wichita Lineman, Desperado. Michael Heffernan and I did a splendid version, I think, of "My Way" at our friends' Mark & Emoke's wedding.

4) The director of the Arkansas MFA program, and his wife (an elementary school teacher), both in their early to mid sixties, did keg stands at said wedding. As did I. As did the groom. As did (I think, but am not totally certain) the bride.

5) In the year between undergrad at College of the Ozarks and my MFA at University of Arkansas, my friend Riley and I rented a trailer outside of Branson, often sharing the trailer with a handful of friends at different points, including Riley's girlfriend at the time, April McIntosh. Below is a picture of myself, Riley, our friend Chris, April, and our friend Eda at C of O dance.

Chris and Eda are now married, with child. Riley is now in Minnesota, beginning his fortune in computers. I am, sadly enough, a poetry blogger. April? April is a Deal-or-No Deal girl, and is also now starring as Daisy Duke in the sequel to the Dukes of Hazzard movie.

________

My good friend Micah has the following quote from Barack Obama:

"In the back-and-forth between Clinton and Gingrich, and in the elections of 2000 and 2004, I sometimes felt as if I were watching the psychodrama of the Baby Boom generation - a tale rooted in old grudges and revenge plots hatched on a handful of campuses long ago - played out on the national stage."

School of Quietude and School of the Post-Avant, anyone? Or, to be less Silliman-centric (he's certainly not the only one, just the readiest example), replace Clinton with usual suspect L, & Gingrich with usual suspect P.

________

I've always been a casual subscriber of the oft-noted deep underlying similarities between much country and hip-hop; Ice Cube/Folsom Prison, etc.

As though to seal the deal:

(thanks to L. Amelia Raley for the lead on the above)

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)